Originally posted on NaturalStrength.com on 01 February 2002 *Illustrations are randomly selected from the book (too numerous to post them all) and are not necessarily from the same chapter.

One day, several years ago, I took a professional "Strong Man" named Herold into my factory to inquire about a special barbell which he had ordered. In order to make the particular kind of bell he wanted, we had to fit a piece of hollow pipe over a solid steel bar. Just before we entered the shop, one of the workmen had started to drive the bar through the piece of pipe; but there

must have been some obstruction inside the pipe, because the bar stuck half-way. The workman was about to put the pipe in a vise so that he could remove the bar when "Herold" intervened. He grasped one end of the pipe in his right hand and told the workman to take hold of the projecting steel bar and pull it out. The "Strong Man" stood with his right foot slightly advanced, and his right elbow close to his side. The workman, who was a husky fellow, took hold of the projecting steel rod in both his hands and gave several tremendous heaves; but although he used every part of his weight and strength, he could not pull the bar out of the pipe. So I added my weight to his, and by a great effort we managed to draw the bar out. Meanwhile, "Herold" stood as though he were carved out of bronze. Even when both of us were pulling against him we never shook him a particle, and neither did we draw his right elbow a fraction of an inch from his side. He held the end of the iron pipe in his hand just as securely as though it had been put in the vise. I want you to bear this story in mind, for I will refer to it several times later on in this book. At this time, I wish to use it as an illustration of the difference between arm strength, and general bodily strength.

When the author of a novel wishes to give his readers an idea of the hero's strength, he says that his hero is "as strong as two or three ordinary men." That is one of those statements which is very easy to make and very hard to prove. In the first place, it raises in your mind the question, "How strong is the ordinary man?" That is something that no one can tell you. In order to

know the answer, it would be necessary to test at least 100,000 men at exactly the same stunts and under exactly the same conditions. All I can tell you is that the available man is not half as strong as he ought to be, or as he could be if he were properly trained.

Now, take the case of the "Strong Man" referred to above. Undoubtedly that man could out-pull any two ordinary men, although he weighed but 160 lbs., and the two of us, who pulled against him, weighed 175 lbs. apiece. If you, who read this book, had seen this "Strong Man," you would have at once exclaimed about his marvelous arms, which measured nearly 17 inches around the biceps; and it is equally probable that you would have ascribed all his strength to his arms. But his right arm, mighty as it was, was doing only part of the work in pulling against us. It was the great strength of the muscles on the right side of his upper back which enabled him to keep his right elbow against his side. If he had been weak in the back, we would have toppled him over on his face at the first pull; but his back was so strong that we could not make him bend forward the least trifle at the waist. If his legs had been weak, we would have slid him along the floor, while as a matter of fact, his feet gripped the ground so strongly that we could not budget him an inch from his original position.

Now, this man was stronger than two average men. In fact, he was probably about as strong as two lumbermen weighing 200 lbs. each. (I had many opportunities to observe his prodigious power.) In a private gymnasium in Buffalo, there was a strength-testing device in the form of an old-fashioned wagon spring. This spring was placed a few inches above the floor in its

normal position; a chain with a handle was fastened to the lower arm of the spring; and the athlete whose strength was to be tested straddled the spring and pulled upward on the chain, so as to bring the two sides of the spring closer together. Across the middle of the spring was a gauge graduated in one-sixteenths of an inch. This test gave a good idea of the ability of a man to raise heavy weights from the ground. The ordinary man could compress the spring about three-eighths of an inch. Some very strong workmen had compressed it to as much as three-quarters of an inch. Herold compressed it one and one-half inches; and I know that to be a fact, because another "Strong Man" told me that he, himself, had been able to compress it only one and one-quarter inches, and referred to H.'s pull as a record. Now, this first lifter (Herold) was not by any means the strongest man in the world, although he was one of the very best in his class. He weighed about 160 lbs., and was just about as strong as either Herman or Kurt Saxon; and while most of his lifting records were just as good as those of any other 160-lb.

lifter, they fell considerably short of the records made by the giants in the lifting game. Nevertheless, he could have fairly been described as being stronger than two ordinary men.

It is very hard for the ordinary citizen to gauge the strength of a real "Strong Man." He goes to a vaudeville show to see a "Strong Act," and he watches the performer stoop under a platform on which fifteen or twenty man are standing, and lift the whole weight on his back. Mr. Ordinary Citizen has never tried this stunt but doubts whether he could raise 500 lbs. in that

way, and so concludes that this performer is many times as strong as he is. Next, he sees the performer take a big barbell weighing 250 lbs., and slowly push it above the head with one hand. This is a stunt that the ordinary citizen knows something about. He has probably tried and failed to put up a 50-lb. weight, so that the performer's 250-lb. lift impresses him greatly. It

will probably surprise you when I tell you that the ordinary man, after a few months of the right kind of training, can develop enough strength to put up 150 lbs. with one hand, and to raise 2,000 lbs. on his back in a "platform-lift." that is enough to make you gasp; I mean you, who are reading these lines. You have always considered yourself as "just the average individual," and at first you cannot grasp the idea that it would be possible for you to learn to accomplish Herculean feats of strength. Yet I, who have seen so many "ordinary citizens" become able to do stunts of this kind, can assure you that your possibilities are, in all likelihood, just as great as those of any other average citizen.

In his book on Physical Education, Dr. Felix Oswald said that one company of soldiers in the Middle Ages would contain more "Strong Men" than would be found in a modern army corps. I cannot agree with this statement. I will admit that possibly the average man of three hundred years ago was stronger than the average man of today, because in those days there were no labor-saving devices, and practically every man had to use his muscles a great deal more than the average man of today uses his. Nevertheless, the strongest men of today are just as strong or stronger than the "Strong Men" of three hundred years ago.

For example, I have a collection of books dealing with the subject of strength, and almost every one of those books starts off by telling you of the wonderful feats of strength accomplished by the mighty men of the past. One man who is always mentioned is Thomas Topham, who was born in London in 1710. When Topham was thirty-one, he made a lift of 1836 lbs. Three barrels of water were chained together. Topham stood on a platform above the barrels, and around his neck was a leather strap which was attached to a chain. This chain passed through a hole in the platform on which he was standing, and was coupled to the chain that bound the barrels together. Topham bent his legs and back slightly and placed his hands on a couple of braces. Then, by simultaneously straightening his arms, back, and legs, he lifted the barrels a couple of inches from the ground. The writers of the books I mentioned always recite this feat as something incredible, and certainly it seems to have been sufficient to preserve Topham's name and fame as a "strong man."

One Saturday afternoon, early in 1917, I had a number of celebrated lifters come to my factory and give an exhibition before an audience of about one hundred experts. Most of the lifting was done with barbells, and one or two records were created on that afternoon. In the factory we had a lifting platform (the one shown in Fig. 3). This platform, as you can see by looking at the pictures, is a double affair. The lifter stands on the upper platform and raises the lower one. After the regular exhibition was over, one of the lifters wished to try his strength at lifting with a harness around the neck. We did not use barrels of water but we piled 50-lb. weights on the bottom platform. This man had never attempted this lift before so we started off with a moderate weight. After he had made a lift we would throw more weights on the bottom platform. He went as high as 2400 lbs. Neither I nor anyone else present considered that lift extraordinary. We fully expected him to lift that much, and every experienced lifter present knew that if he had practiced the lift for a few weeks, he could do 3000 lbs. When I wrote a description of the exhibition for the STRENGTH Magazine, I did not even mention that stunt; but the fact remains that this man (Adolph Nordquest) lifted 550 lbs. more than Topham did; so if Topham was the strongest man of his day, then "Strong Men" must have improved since that time.

In this book I will talk a great deal about lifters and lifting, which means that I will have to say a great deal about heavy barbells and dumbbells; but I do not mean you to think that I claim it is only lifters and barbell users who are gifted with superstrength. As a matter of fact, superstrength is not a gift of nature. If it were, there would be no use of writing this book because, if great strength was the monopoly of a few favored individuals, what would be the use of you trying to acquire such strength? For every man who inherits great strength, or who possesses great strength by virtue of having an unusually large and powerfully made body, there are dozen other men who have deliberately and purposely made themselves strong. I have seen laborers, farmers, football players, physicians, singers, artists and business men who were wonderfully built and tremendously strong; but every one of these men could have been improved by a course of scientific training. To balance that, I have seen scores of men and boys who started with below- average development, and very little strength, who have absolutely converted themselves into "Strong Men." All these individuals got their strength, health and development by practicing with adjustable barbells.

Of course, there are lots of men who are wonderfully strong who have never seen a barbell. I am personally acquainted with many such men; but I must say that there is not one among them whom I could not have made still stronger by putting him on a special training program with weights. On the other hand, I have never seen a man who was naturally weak get into the "Strong Man" class except by the use of weights.

There are some authorities who seem to think that it is foolish for any man to try to improve the body to any great extent; and such authorities are apt to speak in a slighting way of what they call"made" strong men. When I was younger, such remarks used to worry me; but in the last twenty years I have seen so many of these "made" strong men sweep aside the lifting-records made by the natural giants that I have come to the conclusion that "made" strength is just as valuable and lasting as is natural, or inherited, strength.

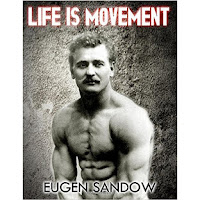

The greatest French authority on the subject of strength is Prof. Des Bonnet. His book, "The Kings of Strength," contains a description (with pictures) of several hundred of the most celebrated "strong men" of the last seventy-five years. In the body of this book you will find pictures of men like Sandow, Arthur Saxon, Hackenschmidt, and many other celebrated athletes who are

familiar to you as being among the strongest men in recent history. In the back of his book Des Bonnet has a special section devoted to two men whom he calls "super-athletes"; and these two men were Louis Cyr, of Canada, and Apollon, of France. He places them in a class by themselves.

Now, as many of you are aware, Saxon, Sandow, Hackenschmidt, and many of the other celebrated "Strong Men" are of average height; and their unusual power is due to the great size and strength of their muscles. Cyr and Apollon were giants. Cyr stood 6 feet and weighed over 300 lbs., and was built on a vastly larger mold than the average "Strong Man." Apollon stood well over 6 feet in height and had a tremendous frame. Undoubtedly both of these men were giants in strength as well as being giants in size; but, just the same, if we go by the records, they do not seem to have been able to deliver more strength than did some of their smaller rivals. For example, Cyr's best record in the two-arm jerk was 345 lbs., Arthur Saxon, who weighed 100 lbs. less than Cyr, also did 345 lbs. in that particular lift. It is true that Cyr lifted the bell in one motion from the floor to the chest, before tossing it to arms' length above his head; whereas Saxon had to raise the bell in two movements to his chest. Nevertheless, he raised it just as much above his head as Cyr did. Two yeas ago I saw Henry Steinborn, who is only a little bit heavier than Saxon, raise in one motion to the chest, and then jerk aloft with both arms, a barbell weighing 347 lbs.; thereby beating Cyr's record. A few nights later some friends of mine saw Steinborn raise 375 lbs. in the same style.

Again, Cyr's best record in the one-arm press is 273 lbs.; and that mark has been beaten by a dozen smaller man. I admit that these men use a style which is different from the method Cyr used; but it can't be denied that some of these men have beaten Cyr's record by anywhere from 20 to 50 lbs.; and in the one-arm press the palm goes to the man who can put up the most weight. Cyr, unquestionably, had bigger muscles and a bigger frame and more natural strength than most lifters have; but he could not exert that strength to much advantage, except when he was in certain positions.

The bodily strength possessed by the so-called "Strong Men," whether amateur or professional, is vastly greater than the strength possessed by the available gymnast, track athlete, oarsman, football player, or workman. The "Strong Man" has a different kind of strength. His arms may be no bigger than those of a Roman-ring performer; his legs may be no bigger than those of a great football player; but he has a bodily strength which is not possessed by any other class of athlete; and this bodily strength is due, first, to the perfect development of every muscle, and, second, to the ability of making those muscles coordinate. As I go on writing these chapters, I intend to continually hammer away in an endeavor to "put over" this idea of bodily strength, as contrasted to arm strength. For most of you, I know, have the fixed idea that a "Strong Man" is strong only because he has such wonderful arms.

Let me tell you another story: this time about an amateur. This man was walking with three companions when they came to a gate in a high iron fence. The amateur "Strong Man" slipped through the gate; slammed it shut; and then invited his three friends to open it. He stretched his arms straight out in front of him, and with each hand grasping one of the upright iron rods in the gate leaned forward and braced himself in the position shown in the illustration (Fig. 9). After a terrific struggle, which lasted a couple of minutes, the other three men succeeded in pushing the gate open; but they did not push the athlete over backwards. He kept himself in the same position, although his feet gradually slipped backwards. It was only his extraordinary

bodily strength that enabled him to exert as much pressure against one side of the gate as his three friends combined could exert against the other side. His arms did very little of the work; they were held rigidly straight, and merely transmitted the pressure exerted by the flexed muscles of his legs and body. On top of that, he applied his strength scientifically. If he had

arched his back or straightened the advanced leg, he would soon have been toppled over backwards. Here is another man who may not have been as strong as three ordinary men, but he certainly was as strong as two.

I could tell you a dozen other such stories; as, for example, how Cyr leaned his mighty shoulders against the end of a loaded freight car and, walking backwards, pushed that car up a slight grade, a stunt in which the arms were not used at all. How other athletes managed to lift hundreds, and even thousands of pounds by the strength of their legs; but I will bring those

stories in where they belong.